- Author:

- Columbus State Community College

- Subject:

- U.S. History

- Material Type:

- Module

- Provider:

- Columbus State Community College

- Tags:

- License:

- Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike

- Language:

- English

- Media Formats:

- Downloadable docs, Text/HTML

Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union (1860)

Howell Cobb to J.D. Hoover (1868)

Jourdon Anderson Writes His Former Master (1865)

Sand Creek Massacre (1864)

HIST 1151 American History to 1877 Primary Source Readings 6: A House Divided and Rebuilt

Overview

A collection of primary source readings for American History to 1877.

Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union (1860)

The primary source readings in this course align with CSCC's version of The American Yawp, Volume 1, which is derived from the The American Yawp open textbook by Stanford University Press. While the original The American Yawp is accompanied by its own primary source reader called The American Yawp Reader, the selection of primary sources you will find in this course differ somewhat in that some of the text excerpts are from the same sources but might feature a different selection from the text. Some of the primary sources in this course are in addition to those found in The American Yawp Reader.

This collection is a work in progress. As introductions, annotations, and "Questions to Consider" are added, updates will be reflected. Users are also welcome to download the Word version of the reading then add or revise the introductions, annotations, or questions.

To take this course for credit, register at Columbus State Community College.

This work, except where otherwise indicated, by Christianna Hurford at Columbus State Community College is licensed CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.

There are not yet introductions to all the readings in this unit, though we anticipate adding introductions following Autumn 2019 semester.

Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union (1860)

Introduction (Secondary Source)[1]

This document outlines the stated reasons why the South Carolina state government separated from the United States of America, including the accusation that the Federal Government violated the U.S. Constitution and encroached upon the reserved rights of the States.

Questions to Consider:

- Context: Who is the author(s) (include a brief bio)? When did s/he write the piece (include some brief context)? Who is the audience? What was the agenda?

- According to this document, what are the reasons that South Carolina seceded from the union? How do they use both the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence to defend this position?

- Why does the document highlight the phrase “free sovereign and independent states?”

- How does this document view the election of Lincoln in 1860 and why? Significance?

- What insights does this document have to offer about American society? Be Specific! [please be sure to consider author, agenda, bias, etc.]

Primary Source[2]

Confederate States of America - Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

The people of the State of South Carolina, in Convention assembled, on the 26th day of April, A.D., 1852, declared that the frequent violations of the Constitution of the United States, by the Federal Government, and its encroachments upon the reserved rights of the States, fully justified this State in then withdrawing from the Federal Union; but in deference to the opinions and wishes of the other slaveholding States, she forbore at that time to exercise this right. Since that time, these encroachments have continued to increase, and further forbearance ceases to be a virtue.

And now the State of South Carolina having resumed her separate and equal place among nations, deems it due to herself, to the remaining United States of America, and to the nations of the world, that she should declare the immediate causes which have led to this act.

In the year 1765, that portion of the British Empire embracing Great Britain, undertook to make laws for the government of that portion composed of the thirteen American Colonies. A struggle for the right of self-government ensued, which resulted, on the 4th of July, 1776, in a Declaration, by the Colonies, "that they are, and of right ought to be, FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES; and that, as free and independent States, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent States may of right do."

They further solemnly declared that whenever any "form of government becomes destructive of the ends for which it was established, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute a new government." Deeming the Government of Great Britain to have become destructive of these ends, they declared that the Colonies "are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."

In pursuance of this Declaration of Independence, each of the thirteen States proceeded to exercise its separate sovereignty; adopted for itself a Constitution, and appointed officers for the administration of government in all its departments-- Legislative, Executive and Judicial. For purposes of defense, they united their arms and their counsels; and, in 1778, they entered into a League known as the Articles of Confederation, whereby they agreed to entrust the administration of their external relations to a common agent, known as the Congress of the United States, expressly declaring, in the first Article "that each State retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every power, jurisdiction and right which is not, by this Confederation, expressly delegated to the United States in Congress assembled."

Under this Confederation the war of the Revolution was carried on, and on the 3rd of September, 1783, the contest ended, and a definite Treaty was signed by Great Britain, in which she acknowledged the independence of the Colonies in the following terms: "ARTICLE 1-- His Britannic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz: New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, to be FREE, SOVEREIGN AND INDEPENDENT STATES; that he treats with them as such; and for himself, his heirs and successors, relinquishes all claims to the government, propriety and territorial rights of the same and every part thereof."

Thus were established the two great principles asserted by the Colonies, namely: the right of a State to govern itself; and the right of a people to abolish a Government when it becomes destructive of the ends for which it was instituted. And concurrent with the establishment of these principles, was the fact, that each Colony became and was recognized by the mother Country a FREE, SOVEREIGN AND INDEPENDENT STATE.

In 1787, Deputies were appointed by the States to revise the Articles of Confederation, and on 17th September, 1787, these Deputies recommended for the adoption of the States, the Articles of Union, known as the Constitution of the United States.

The parties to whom this Constitution was submitted, were the several sovereign States; they were to agree or disagree, and when nine of them agreed the compact was to take effect among those concurring; and the General Government, as the common agent, was then invested with their authority.

If only nine of the thirteen States had concurred, the other four would have remained as they then were-- separate, sovereign States, independent of any of the provisions of the Constitution. In fact, two of the States did not accede to the Constitution until long after it had gone into operation among the other eleven; and during that interval, they each exercised the functions of an independent nation.

By this Constitution, certain duties were imposed upon the several States, and the exercise of certain of their powers was restrained, which necessarily implied their continued existence as sovereign States. But to remove all doubt, an amendment was added, which declared that the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States, respectively, or to the people. On the 23d May , 1788, South Carolina, by a Convention of her People, passed an Ordinance assenting to this Constitution, and afterwards altered her own Constitution, to conform herself to the obligations she had undertaken.

Thus was established, by compact between the States, a Government with definite objects and powers, limited to the express words of the grant. This limitation left the whole remaining mass of power subject to the clause reserving it to the States or to the people, and rendered unnecessary any specification of reserved rights.

We hold that the Government thus established is subject to the two great principles asserted in the Declaration of Independence; and we hold further, that the mode of its formation subjects it to a third fundamental principle, namely: the law of compact. We maintain that in every compact between two or more parties, the obligation is mutual; that the failure of one of the contracting parties to perform a material part of the agreement, entirely releases the obligation of the other; and that where no arbiter is provided, each party is remitted to his own judgment to determine the fact of failure, with all its consequences.

In the present case, that fact is established with certainty. We assert that fourteen of the States have deliberately refused, for years past, to fulfill their constitutional obligations, and we refer to their own Statutes for the proof.

The Constitution of the United States, in its fourth Article, provides as follows: "No person held to service or labor in one State, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up, on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due."

This stipulation was so material to the compact, that without it that compact would not have been made. The greater number of the contracting parties held slaves, and they had previously evinced their estimate of the value of such a stipulation by making it a condition in the Ordinance for the government of the territory ceded by Virginia, which now composes the States north of the Ohio River.

The same article of the Constitution stipulates also for rendition by the several States of fugitives from justice from the other States.

The General Government, as the common agent, passed laws to carry into effect these stipulations of the States. For many years these laws were executed. But an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery, has led to a disregard of their obligations, and the laws of the General Government have ceased to effect the objects of the Constitution. The States of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa, have enacted laws which either nullify the Acts of Congress or render useless any attempt to execute them. In many of these States the fugitive is discharged from service or labor claimed, and in none of them has the State Government complied with the stipulation made in the Constitution. The State of New Jersey, at an early day, passed a law in conformity with her constitutional obligation; but the current of anti-slavery feeling has led her more recently to enact laws which render inoperative the remedies provided by her own law and by the laws of Congress. In the State of New York even the right of transit for a slave has been denied by her tribunals; and the States of Ohio and Iowa have refused to surrender to justice fugitives charged with murder, and with inciting servile insurrection in the State of Virginia. Thus the constituted compact has been deliberately broken and disregarded by the non-slaveholding States, and the consequence follows that South Carolina is released from her obligation.

The ends for which the Constitution was framed are declared by itself to be "to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity."

These ends it endeavored to accomplish by a Federal Government, in which each State was recognized as an equal, and had separate control over its own institutions. The right of property in slaves was recognized by giving to free persons distinct political rights, by giving them the right to represent, and burthening them with direct taxes for three-fifths of their slaves; by authorizing the importation of slaves for twenty years; and by stipulating for the rendition of fugitives from labor.

We affirm that these ends for which this Government was instituted have been defeated, and the Government itself has been made destructive of them by the action of the non-slaveholding States. Those States have assume the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions; and have denied the rights of property established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution; they have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery; they have permitted open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace and to eloign the property of the citizens of other States. They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection.

For twenty-five years this agitation has been steadily increasing, until it has now secured to its aid the power of the common Government. Observing the forms of the Constitution, a sectional party has found within that Article establishing the Executive Department, the means of subverting the Constitution itself. A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery. He is to be entrusted with the administration of the common Government, because he has declared that that "Government cannot endure permanently half slave, half free," and that the public mind must rest in the belief that slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction.

This sectional combination for the submersion of the Constitution, has been aided in some of the States by elevating to citizenship, persons who, by the supreme law of the land, are incapable of becoming citizens; and their votes have been used to inaugurate a new policy, hostile to the South, and destructive of its beliefs and safety.

On the 4th day of March next, this party will take possession of the Government. It has announced that the South shall be excluded from the common territory, that the judicial tribunals shall be made sectional, and that a war must be waged against slavery until it shall cease throughout the United States.

The guaranties of the Constitution will then no longer exist; the equal rights of the States will be lost. The slaveholding States will no longer have the power of self-government, or self-protection, and the Federal Government will have become their enemy.

Sectional interest and animosity will deepen the irritation, and all hope of remedy is rendered vain, by the fact that public opinion at the North has invested a great political error with the sanction of more erroneous religious belief.

We, therefore, the People of South Carolina, by our delegates in Convention assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, have solemnly declared that the Union heretofore existing between this State and the other States of North America, is dissolved, and that the State of South Carolina has resumed her position among the nations of the world, as a separate and independent State; with full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent States may of right do.

Adopted December 24, 1860

[1] “Introduction to Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union” by Docs Teach is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA.

[2] "Confederate States of America - Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union" by South Carolina Convention is in the Public Domain.

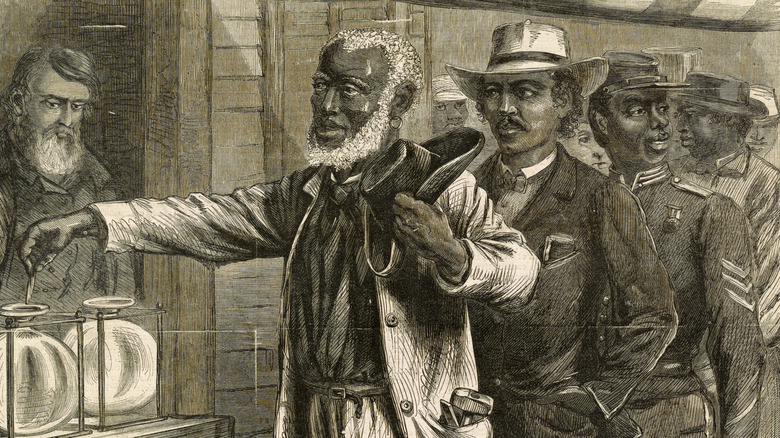

Image: Alfred R. Waud, The First Vote, November 1867. Library of Congress.

Charlotte Forten Teachers Freed Children in South Carolina (1864)

Charlotte Forten Teachers Freed Children in South Carolina (1864)

Charlotte Forten

Introduction (Secondary Source)[1]

Charlotte Forten was born into a wealthy black family in Philadelphia. After receiving an education in Salem, Massachusetts, Forten became the first black American hired to teach white students. She lent her educational expertise to the war effort by relocating to South Carolina in 1862 with the goal of educating former slaves. This excerpt from her diary explains her experiences during this time.

Questions to Consider:

- Context: Who is the author(s) (include a brief bio)? When did s/he write the piece (include some brief context)? Who is the audience? What was the agenda?

- Why was her first day of school trying and what glimpse does this offer into the reality of 19th century life?

- How does her experience with educating blacks in the South run contrary to arguments that sought to perpetuate slavery? What does this suggest about identity of both blacks and whites?

- What other topics did Forten discuss with her pupils and why?

- What insights does this document have to offer about American society? Be Specific! [please be sure to consider author, agenda, bias, etc.]

Primary Source[2]

The first day at school was rather trying. Most of my children were very small, and consequently restless. Some were too young to learn the alphabet. These little ones were brought to school because the older children — in whose care their parents leave them while at work — could not come without them. We were therefore willing to have them come, although they seemed to have discovered the secret of perpetual motion, and tried one’s patience sadly. But after some days of positive, though not severe treatment, order was brought out of chaos, and I found but little difficulty in managing and quieting the tiniest and most restless spirits. I never before saw children so eager to learn, although I had had several years’ experience in New England schools. Coming to school is a constant delight and recreation to them. They come here as other children go to play. The older ones, during the summer, work in the fields from early morning until eleven or twelve o’clock, and then come into school, after their hard toil in the hot sun, as bright and as anxious to learn as ever.

Of course there are some stupid ones, but these are the minority. The majority learn with wonderful rapidity. Many of the grown people are desirous of learning to read. It is wonderful how a people who have been so long crushed to the earth, so imbruted as these have been, — and they are said to be among the most degraded negroes of the South, — can have so great a desire for knowledge, and such a capability for attaining it. One cannot believe that the haughty Anglo Saxon race, after centuries of such an experience as these people have had, would be very much superior to them. And one’s indignation increases against those who, North as well as South, taunt the colored race with inferiority while they themselves use every means in their power to crush and degrade them, denying them every right and privilege, closing against them every avenue of elevation and improvement. Were they, under such circumstances, intellectual and refined, they would certainly be vastly superior to any other race that ever existed.

After the lessons, we used to talk freely to the children, often giving them slight sketches of some of the great and good men. Before teaching them the “John Brown” song, which they learned to sing with great spirit. Miss T. told them the story of the brave old man who had died for them. I told them about Toussaint, thinking it well they should know what one of their own color had done for his race. They listened attentively, and seemed to understand. We found it rather hard to keep their attention in school. It is not strange, as they have been so entirely unused to intellectual concentration. It is necessary to interest them every moment, in order to keep their thoughts from wandering. Teaching here is consequently far more fatiguing than at the North. In the church, we had of course but one room in which to hear all the children; and to make one’s self heard, when there were often as many as a hundred and forty reciting at once, it was necessary to tax the lungs very severely.

My walk to school, of about a mile, was part of the way through a road lined with trees, — on one side stately pines, on the other noble live-oaks, hung with moss and canopied with vines. The ground was carpeted with brown, fragrant pine-leaves; and as I passed through in the morning, the woods were enlivened by the delicious songs of mocking-birds, which abound here, making one realize the truthful felicity of the description in “Evangeline,” —

“The mocking-bird, wildest of singers,

Shook from his little throat such floods of delirious music

That the whole air and the woods and the waves seemed silent to listen.”

The hedges were all aglow with the brilliant scarlet berries of the cassena, and on some of the oaks we observed the mistletoe, laden with its pure white, pearl-like berries. Out of the woods the roads are generally bad, and we found it hard work plodding through the deep sand.

[1]“Introduction to Charlotte Forten Teaches Freed Children in South Carolina, 1864” from The American Yawp Reader by Stanford University Press is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0.

[2] Charlotte Forten, “Life on the Sea Islands,” Atlantic Monthly: A Magazine of Literature, Art, and Politics, Volume XIII (Boston: 1864), 591-592.

Primary source is in the public domain.

Sand Creek Massacre (1864)

Sand Creek Massacre (1864)

S.S. Soule and Joe A. Crammer

Introduction (Secondary Source)[1]

Captain Silas S. Soule and Lieutenant Joseph A. Cramer of the 1st Colorado (U.S.) Volunteer Cavalry put their military careers -and lives –at risk by refusing to fire during the attack against a peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho village at Sand Creek, November 29, 1864.With their companies backing them up, they purposely took little or no part in the massacre of people they knew. Afterward, both men wrote letters to their former commander Major Edward “Ned” Wynkoop, describing the horrors they had witnessed and condemning the leadership of Colonel John M. Chivington, the expedition’s commander. These letters led to investigations by two congressional committees and an army commission, which changed history’s judgment of Sand Creek from a battle to a massacre of men, women, and children. Several weeks after Soule testified before the commission, he was shot in the streets of Denver. His murderers, although known, were never brought to justice. These graphic and disturbing letters disappeared, only to resurface in 2000 in time to help convince the U.S. Congress to pass legislation establishing the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. The power of these letters, then and now, lies in their simple honesty, their moral courage and the determination of two soldiers who wanted to see justice done.

Questions to Consider:

- Context: Who is the author(s) (include a brief bio)? When did s/he write the piece (include some brief context)? Who is the audience? What was the agenda?

- How does the letter describe the Indians camped at Sand Creek and why is this important?

- Why does the author refuse to fire on the Indians? Significance?

- How do the actions of the men portrayed here run contrary to the identity the author expected of such men?

- What insights does this document have to offer about American society? Be Specific! [please be sure to consider author, agenda, bias, etc.]

Primary Source[2]

Fort Lyon, C.T. December 14, 1864

Dear Ned:

Two days after you left here the 3rdReg. with a Battalion of the 1st arrived here, having moved so secretly that we were not aware of their approach until they had Pickets around the post, allowing no one to pass out! They arrested Capt. Bent and John Vogle and placed guards around their houses. Then they declared their intention to massacre the friendly Indians camped on Sand Creek. Major Anthony gave all information, and eagerly joined in with Chivington and Co. and ordered Lieut. Cramer with his whole Co. to join the command. As soon as I knew of their movement I was indignant as you would have been were you here, and were you here, and went to Cannon’s room, where a number of officers of the 1st and 3rd were congregated and told them that any man who would take part in the murders, knowing the circumstances as we did, was a low lived cowardly son of a bitch. Capt. J.J. Johnson and Lieut. Harding went to camp and reported to Chiv, Downing and the whole outfit what I had said, and you can bet hell was to pay in camp. Chiv and all hands swore they would hang me before they moved camp, but I stuck it out, and all the officers of the post, except Anthony backed me.

We arrived at Black Kettle and Left Hand’s Camp at day light. Lieut. Wilson with Co.s “C”, “E” & “G” were ordered to in advance to cut off their herd. He made a circle to the rear and formed a line 200 yds from the village, and opened fire. Poor old John Smith and Louderbeck ran out with white flags but they paid no attention to them, and they ran back into the tents. Anthony(indecipherable) with Co’s “D” “K” & “G”, to within one hundred yards and commenced firing. I refused to fire and swore that none but a coward would. For by this time hundreds of women and children were coming towards us and getting on their knees for mercy. Anthony shouted, “kill the sons of bitches” Smith and Louderbeck came to our command, although I am confident there were 200 shots fired at them, for I heard an officers say that Old Smith and any one who sympathized with the Indians, ought to be killed and now was a good time to do it. The Battery then came up in our rear, and opened on them. I took my comp’y across the Creek, and by this time the whole of the 3rdand the Batteries were firing into them and you can form some idea of the slaughter. When the Indians found that there was no hope for them they went for the Creek, and buried themselves in the Sand and got under the banks and some of the Bucks got their bows and a few rifles and defended themselves as well as they could. By this time there was no organization among our troops, they were a perfect mob –every man on his own hook. My Co. was the only one that kept their formation, and we did not fire a shot.

The massacre lasted six or eight hours, and a good many Indians escaped. I tell you Ned it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized. One squaw was wounded and a fellow took a hatchet to finish her, she held her arms up to defend her, and he cut one arm off, and held the other with one hand and dashed the hatchet through her brain. One squaw with her two children, were on their knees begging for their lives of a dozen soldiers, within ten feet of them all, firing –when one succeeded in hitting the squaw in the thigh, when she took a knife and cut the throats of both children, and then killed herself. One old squaw hung herself in the lodge –there was not enough room for her to hang and she held up her knees and choked herself to death. Some tried to escape on the Prairie, but most of them were run down by horsemen. I saw two Indians hold one of another’s hands, chased until they were exhausted, when they kneeled down, and clasped each other around the neck and were both shot together. They were all scalped, and as high as half a dozen taken from one head. They were all horribly mutilated. One woman was cut open and a child taken out of her, and scalped.

White Antelope, War Bonnet and a number of others had Ears and Privates cut off. Squaw’s snatches were cut out for trophies. You would think it impossible for white men to butcher and mutilate human beings as they did there, but every word I have told you is the truth, which they do not deny. It was almost impossible to save any of them. Charly Autobee save John Smith and Winsers squaw. I saved little Charlie Bent. Geo. Bent was killed [George Bent was wounded but survived} Jack Smith was taken prisoner, and murdered the next day in his tent by one of Dunn’s Co. “E”. I understand the man received a horse for doing the job. They were going to murder Charlie Bent, but I run him into the Fort. They were going to kill Old Uncle John Smith, but Lt. Cannon and the boys of Ft. Lyon, interfered, and saved him. They would have murdered Old Bents family if Col. Tappan had not taken the matter in hand. Cramer went up with twenty (20) men, and they did not like to buck against so many of the 1st. Chivington has gone to Washington to be made General, I suppose, and get authority to raise a nine months Reg’t to hunt Indians. He said Downing will have me cashiered if possible. If they do I want you to help me. I think they will try the same for Cramer for he has shot his mouth off a good deal, and did not shoot his pistol off in the Massacre. Joe has behaved first rate during this whole affair. Chivington reports five or six hundred killed, but there were not more than two hundred, about 140 women and children and 60 Bucks. A good many were out hunting buffalo. Our best Indians were killed. Black Kettle, One Eye, Minnemic and Left Hand. Geo. Pierce of Co. “F” was killed trying to save John Smith. There was one other of the 1st killed and nine of the 3rd all through their own fault. They would get up to the edge of the bank and look over, to get a shot at an Indian under them. When the women were killed the Bucks did not seem to try and get away, but fought desperately. Charly Autobeee wished me to write all about it to you. He says he would have given anything if you could have been there. I suppose [Joe] Cramer has written to you, all the particulars, so I will write half. Your family is well. Billy Walker, Co. Tappan, Wilson (who was wounded in the arm) start for Denver in the morning. There is not news I can think of. I expect we will have a hell of a time with Indians this winter. We have (200) men at the post –Anthony in command. I think he will be dismissed when the facts are known in Washington. Give my regards to any friends you come across, and write as soon as possible.

Yours,

SS(signed) S.S. Soule

Ft. Lyon, C. T.

December 19, 1864

Dear Major:

This is the first opportunity I have had of writing you since the great Indian Massacre, and for a start, I will acknowledge I am ashamed to own I was in it with my Co. Col. Chivington came down here with the gallant third known as Chivington Brigade, like a thief in the dark throwing his Scouts around the Post, with instructions to let no one out, without his orders, not even the Commander of the Post, and for the shame, our Commanding Officer submitted. Col. Chivington expected to find the Indians in camp below the Com----(commissary) but the Major Comd'g told him all about where the Indians were, and volunteered to take a Battalion from the Post and Join the Expedition.

Well Col. Chiv. got in about 10 a.m., Nov. 28th and at 8 p.m. we started with all of the 3rd parts of "H" "O" and "E" of the First, in command of Lt. Wilson Co. "K" "D" and "G" in commanding of Major Anthony. Marched all night up Sand, to the big bend in Sandy, about 15 or 20 miles, above where we crossed on our trip to Smoky Hill and came on to Black Kettles village of 103 lodges, containing not over 500 all told, 350 of which were women and children. Three days previous to our going out, Major Anthony gave John Smith, Lowderbuck of Co. "G" and a government driver, permission to go out there and trade with them, and they were in the village when the fight came off. John Smith came out holding up his hands and running towards us, when he was shot at by several, and the word was passed along to shoot him. He then turned back, and went to his tent and got behind some Robes, and escaped unhurt. Lowderbuck came out with a white flag, and was served the same as John Smith, the driver the same. Well I got so mad I swore I would not burn powder, and I did not. Capt. Soule the same. It is no use for me to try to tell you how the fight was managed, only that I think the Officer in Command should be hung, and I know when the truth is known it will cashier him.

We lost 40 men wounded, and 10 killed. Not over 250 Indians mostly women and children, and I think not over 200 were killed, and not over 75 bucks. With proper management they could all have been killed and not lost over 10 men. After the fight there was a sight I hope I may never see again.

Bucks, women, and children were scalped, fingers cut off to get the rings on them, and this as much with Officers as men, and one of those Officers a Major, and a Lt. Col. cut off Ears, of all he came across, a squaw ripped open and a child taken from her, little children shot, while begging for their lives (and all the indignities shown their bodies that was ever heard of) (women shot while on their knees, with their arms around soldiers a begging for their lives.) things that Indians would be ashamed to do. To give you some little idea, squaws were known to kill their own children, and then themselves, rather than to have them taken prisoners. Most of the Indians yielded 4 or 5 scalps. But enough! for I know you are disgusted already. Black Kettle, White Antelope, War Bonnet, Left Hand, Little Robe and several other chiefs were killed. Black Kettle said when he saw us coming, that he was glad, for it was Major Wynkoop coming to make peace. Left Hand stood with his hands folded across his breast, until he was shot saying, "Soldiers no hurt me -soldiers my friends." One Eye was killed; was in the employ of Gov't as spy; came into the Post a few days before, and reported about the Sioux, were going to break out at Learned, which proved true.

After all the pledges made my Major A-to these Indians and then take the course he did. I think as comments are necessary from me; only I will say he has a face for every man he talks. The action taken by Capt. Soule and myself were under protest. Col. A–was going to have Soule hung for saying there were all cowardly Sons of B----s; if Soule did not take it back, but nary take a back with Soule. I told the Col. that I thought it murder to jump them friendly Indians. He says in reply; Damn any man or men who are in sympathy with them. Such men as you and Major Wynkoop better leave the U. S. Service, so you can judge what a nice time we had on the trip. I expect Col. C-and Downing will do all in their power to have Soule, Cossitt and I dismissed. Well, let them work for what they damn please, I ask no favors of them. If you are in Washington, for God’s sake, Major, keep Chivington from being a Bri'g Genl. which he expects. I will send you the Denver Papers with this. Excuse this for I have been in much of a hurry. Very Respectfully, Your Well Wisher (signed) Joe A. Cramer (postscript) John (Jack) Smith was taken prisoner and then murdered. One little child 3 months old was thrown in the feed box of a wagon and brought one days march, and there was left on the ground to perish. Col. Tappan is after them for all that is out. I am making out a report of all from beginning to end, to send to Gen’l Slough, in hopes that he will have the thing investigated, and if you should see him, please speak to him about it, for fear that he has forgotten me. I shall write him nothing but what can be proven. Major I am ashamed of this. I have it gloriously mixed up, but in hopes I can explain it all to you before long. I would have given my right arm had you been here, when they arrived.

Your family are all well.

(signed) Joe A. Cramer

[1] "Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site Resource Bulletin: Conscience and Courage" by National Park Service is in the Public Domain.

[2] "Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site Resource Bulletin: Conscience and Courage" by National Park Service is in the Public Domain.

Jourdon Anderson Writes His Former Master (1865)

Jourdon Anderson Writes His Former Master (1865)

Jourdon Anderson

Introduction (Secondary Source)[1]

Black Americans hoped that the end of the Civil War would create an entirely new world, while white southerners tried to restore the antebellum order as much as they could. Most slave-owners sought to maintain control over their former slaves through sharecropping contracts. P.H. Anderson of Tennessee was one such former slave-owner. After the war, he contacted his former slave Jourdon Anderson, offering him a job opportunity. The following is Jourdon Anderson’s reply.

Questions to Consider:

- Context: Who is the author(s) (include a brief bio)? When did s/he write the piece (include some brief context)? Who is the audience? What was the agenda?

- What insight does this document offer about the relationship between Jourdon Anderson and his master?

- What does Jourdon Anderson say it would take for him to return to and trust his former master? How do you think such demands were received and why?

- What insight does this document offer into the treatment of female enslaved persons? Why does he include this in his letter?

- What insights does this document have to offer about American society? Be Specific! [please be sure to consider author, agenda, bias, etc.]

Primary Source[2]

Dayton, Ohio, August 7, 1865.

To my old Master, Colonel P. H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee.

Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master. Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq.,

Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve—and die, if it come to that—than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters. You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson

[1] "Jourdon Anderson Writes His Former Master, 1865" by Stanford University Press is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/reconstruction/jourdon-anderson-writes-his-former-master-1865/

[2] "Jourdon Anderson Writes His Former Master, 1865" by Stanford University Press is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/reconstruction/jourdon-anderson-writes-his-former-master-1865/

Howell Cobb to J.D. Hoover (1868)

Howell Cobb to J.D. Hoover (1868)

Howell Cobb

Questions to Consider:

- Context: Who is the author(s) (include a brief bio)? When did s/he write the piece (include some brief context)? Who is the audience? What was the agenda?

- Why is the author hesitant to write this letter? What does this suggest about the identity of the nation at this time?

- What is this author’s view on the future? Why? Significance?

- What does he say happened to their property? Why? Significance?

- What insights does this document have to offer about American society? Be Specific! [please be sure to consider author, agenda, bias, etc.]

Primary Source[1]

HOWELL COBB TO J. D. HOOVER, CHAIRMAN.352MACON [GA.],

4 Jany., 1868.

DR. SIR: Your invitation to attend the celebration of the 8th January by the democratic resident committee of Washington City has just been received. It revives pleasant memories of the past—and tempts me to break a self-imposed silence on political questions which I have observed since the close of the War. And yet I hesitate to write—for what I write may not harmonize with the festivities of the occasion which assembles you and I would not mar the happy hours of those who meet to celebrate a national festival under the protecting care of the constitution of our fathers.

We of the ill-fated South realize only the mournful present whose lesson teaches us to prepare for a still gloomier future. To participate in a national festival would be a cruel mockery, for which I frankly say to you I have no heart, however much I may honor the occasion and esteem the association with which I would be thrown.

The people of the south, conquered, ruined, impoverished, and oppressed, bear up with patient fortitude under the heavy weight of their burthens. Disarmed and reduced to poverty, they are power-less to protect themselves against wrong and injustice; and can only await with unbroken spirits that destiny which the future has instore for them. At the bidding of their more powerful conquerors they laid down their arms, abandoned a hopeless struggle, and returned to their quiet homes under the plighted faith of a soldier’s honor that they should be protected so long as they observed the obligations imposed upon them of peaceful law-abiding citizens. Despite the bitter charges and accusations brought against our people, I hesitate not to say that since that hour their bearing and conduct have been marked by a dignified and honorable submission which should command the respect of their bitterest enemy and challenge the admiration of the civilized world. Deprived of our property and ruined in our estates by the results of the war, we have accepted the situation and given the pledge of a faith never yet bro-ken to abide it. Our conquerors seem to think we should accompany our acquiescence with some exhibition of gratitude for the ruin which they have brought upon us. We cannot see it in that light. Since the close of the war they have taken our property of various kinds, sometimes by seizure, and sometimes by purchase,—and when we have asked for remuneration have been informed that the claims of rebels are never recognized by the Government. To this decision necessity compels us to submit; but our conquerors express surprise that we do not see in such ruling the evidence of their kindness and forgiving spirit. They have imposed upon us in our hour of distress and ruin a heavy and burthensome tax, peculiar and limited to our impoverished section. Against such legislation we have ventured to utter an earnest appeal, which to many of their leading spirits indicates a spirit of insubordination which calls for additional burthens. They have deprived us of the protection afforded by our state constitutions and laws, and put life, liberty and property at the disposal of absolute military power. Against this violation of plighted faith and constitutional right we have earnestly and solemnly protested, and our protests have been denounced as insolent;—and our restlessness under the wrong and oppression which have followed these acts has been construed into a rebellious spirit, demanding further and more stringent restrictions of civil and constitutional rights. They have arrested the wheels of State government, paralyzed the arm of industry, engendered a spirit of bitter antagonism on the part of our negro population towards the white people with whom it is the interest of both races they should maintain kind and friendly relations, are now struggling by all the means in their power both legal and illegal, constitutional and unconstitutional, to make our former slaves our masters, bringing these Southern states under the power of negro supremacy. To these efforts we have opposed appeals, protests, and every other means of resistance in our power, and shall continue to do so to the bitter end. If the South is to be made a pandemonium and a howling wilderness the responsibility shall not rest upon our heads. Our conquerors regard these efforts on our part to save ourselves and posterity from the terrible results of their policy and conduct as anew rebellion against the constitution of our country, and profess to be amazed that in all this we have failed to see the evidence of their great magnanimity and exceeding generosity. Standing today in the midst of the gloom and suffering which meets the eye in every direction, we can but feel that we are the victims of cruel legislation and the harsh enforcement of unjust laws. On the other hand our conquerors are amazed that the sufferings of our people create no joy, and the threatened starvation of our wives and children afford no cause for mirth and hilarity, and above all that our hearts do not overflow with gratitude to those who have brought these calamities upon us, and whose policy foreshadows still greater sufferings and gloomier days. We regarded the close of the war as ending the relationship of enemies and the beginning of a new national brother-hood, and in the light of that conviction felt and spoke of constitutional equality. We felt and spoke as freemen and American citizens, and some were bold enough to present their petitions and grievances before the governing power. Such had always been the right and privilege of an American citizen;—but regarding our status in a far different light, such petitions and complaints were denounced in our legislative halls as impertinent and insolent con-duct, and even the representative who offered them was rebuked for his temerity. We claimed that the result of the war left us a state in the Union, and therefore under the protection of the constitution, rendering in return cheerful obedience to its requirements and bearing in common with the other states of the Union the burthens of government, submitting even as we were compelled to do to taxation without representation; but they tell us that a successful war to keep us in the Union left us out of the Union and that the pretension we put up for constitutional protection evidences bad temper on our part and a want of appreciation of the generous spirit which declares that the constitution is not over us for the purpose of protection. It reaches our case only when burthens are to be imposed. If on the other hand we venture to whisper that this theory makes secession an accomplished fact and puts these southern states out of the Union, we stand forthwith charged with a renewal of the old issue and a hidden desire to war upon the integrity of the Union. In such reasoning is found a justification of the policy which seeks to put the South under negro supremacy. Better, they say, to hazard the consequences of negro supremacy in the south with its sure and inevitable results upon Northern prosperity than to put faith in the people of the south who though overwhelmed and conquered have ever showed themselves a brave and generous people, true to their plighted faith in peace and in war, in adversity as in prosperity. If were main silent in the midst of all these conflicting trials and troubles, we are taunted with a cowardly fear that prevents an honest expression of opinion. If on the other hand a brave, and it may be an imprudent spirit, ventures to give expression to his convictions on questions so vitally affecting the very existence of our people, he is threatened with arrest as a disturber of the public peace and the instigator of a new rebellion. Whatever we may do or say is construed into the exhibition of disloyal sentiments and made the pre-text for renewed aggressive legislation. It is one of the strange features of human organization to hate those whom we have wronged, and each additional wrong that we put upon others intensifies the hatred which the first wrong created. In this way alone can I account for the bitterness with which our conquerors have pursued our ruined people. That they do hate us none can doubt who will calmly review the history of the governing power since the close of the war. That it will continue through life I doubt not; and in torment they will raise up their eyes, cursing the good and virtuous who are peacefully reposing in Abraham’s bosom, beyond the reach of their malignity.

When to present trials, troubles and sufferings, you add the threatening promises of the early future, growing out of the impoverished condition of both the white and negro population, you will readily understand that we have no heart for festive scenes, even though they come to us consecrated by the memories which bring to our contemplation the virtues and greatness of the noble old patriot who in his day and generation “filled the measure of his country’s glory.”

Through the gloom and darkness which envelops the South, a ray of light is seen. The appeal made in behalf of the constitution as well as of a ruined people has at length reached the northern heart; and in the recent elections in many of the northern states a response has been spoken which has cheered our hearts and caused a smile even upon the furrowed brow of suffering.

I have never doubted the ultimate verdict which the intelligent and virtuous mind of the north would pronounce when relieved from the baneful influence of passion and prejudice. Fortunately for the North as well as the South the Democratic organization presents the opportunity for concentrating all conservative and constitutional elements in the coming struggle for constitutional liberty. At one time some fears were felt that old prejudices engendered in the party, struggles of the past upon issues now past and gone, would interpose obstacles in the way of that united and concentrated effort so essential to success; but those fears are fast passing away as we see the good and intelligent and virtuous of all parties recognizing the fact that the great battle for the preservation of the constitution must be fought under the banner of that old time-honored party whose records bear the honored names of Jefferson and Jackson.

With an Executive who manifests a resolute purpose to defend with all his power the constitution of his country from further aggression, and a Judiciary whose unspotted record has never yet been tarnished with a base subserviency to the unholy demands of passion and hatred, let us indulge the hope that the hour of the country’s redemption is at hand, and that even in the wronged and ruined South there is a fair prospect for better days and happier hours when our people can unite again in celebrating national festivals as in the olden time.

[1] Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1911, vol. II, The Correspondence of Robert Toombs, Alexander H. Stephens, and Howell Cobb, edited by Ulrich B. Phillips, Portage Publications, pp. 860-864.

The underlying text in this primary source is in the public domain.